Eye For Film >> Movies >> Daughter (2022) Film Review

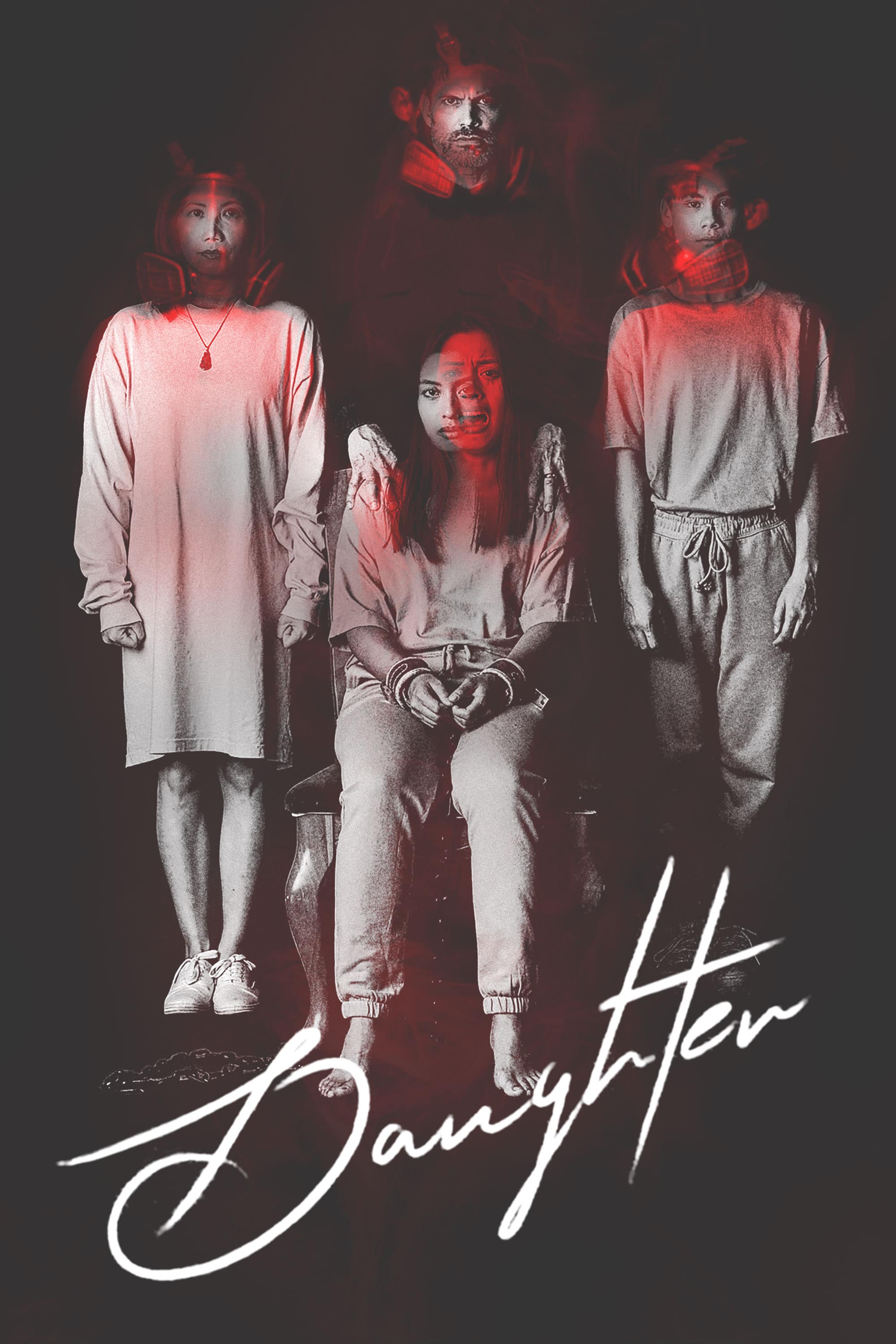

Daughter

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

“It’s easier to give him what he wants,” says Mother.

We have seen what happens when he doesn’t get his way. in the opening scenes, a young woman runs headlong down a dirt road, followed by a car. The car stops at the top of an incline, skylined in imposing style. The Father and the Son get out, easily running the exhausted woman down despite the fact that they’re wearing gas masks. On a patch of grass surrounded by trees, Father strikes again and again. Afterwards, Son apologises. He knows that he should have spotted the signs and spoken up before it came to that. Then they might still be a happy family.

We meet the new Daughter (now played by Vivien Ngô) shortly afterwards, when the bag is taken off her head and her role is explained to her. Father (Casper Van Dien) says that everything in his life revolves around protecting Son (Ian Alexander), and that if she understands that and behaves accordingly, leaving the rot of the outer world behind, she will be perfectly safe. In fact, after two years, he’ll let her go. Nobody will harm or abuse her, as long as she’s good.

A close-up study of the dynamics of power in an absurd but still believable situation (described in the opening credits as ‘based on more fact than fiction’), this is a film inspired by the work of Simone de Beauvoir, played out in a modest home where everything is beige or tan or varnished wood. The windows are covered; the garage is full of gallon bottles of water. The air outside is toxic, Son explains. That’s why people get sick and behave in terrible ways. To keep them safe, Father makes sure that they’re all shackled and the doors are locked before he goes out for supplies. Son passes the time with board games: Outwit, Sorry, Finance and more. Daughter’s job is to play with him and keep him company. One day, says Father, that boy will save the world.

Daughter is smart. She realises that there’s no point in rebelling just for the sake of it, but she watches and she waits, getting to know those around her. The film’s best scenes are those between her and Mother (Elyse Dinh), who has been there much longer, is presumably experiencing a different kind of suffering, and has a very different way of coping. The friction between the two presents an early threat to Father’s treasured peace, even though their shared use of Vietnamese – which he doesn’t speak – would seem to make them allies. Staying out of trouble proves complicated, as it’s difficult to know what Father will be offended by, but as she observes Son’s passion for creative projects, she begins to identify an area in which she can take away some of the patriarch’s power.

Cleverly shot throughout in a style which contributes to the claustrophobia of the family’s environment and speaks to where power is positioned, the film also benefits from a minimal but very effective score. It’s carefully paced, with injections of humour where they’re most needed, and some sharp observations to make about wider society. Some viewers may find the loose ends frustrating but they don’t come across as an oversight, simply as a reminder that, seeing this world through Daughter’s eyes, we can’t expect to make sense of it in its entirety, and there may be still more dreadful possibilities lurking just out of sight.

Ngô and director Corey Deshon have stated that they wanted to create opportunity for Asian American actors and to show that people of colour can make diverse types of films. There’s certainly a lot of talent on display here, and it’s also nice to see Van Dien doing something worthwhile after spending most of his post-Starship Troopers career in three-for-a-pound B-movies. If his name makes you expect more of the same when you come to this, you’re in for a pleasant surprise. Rather than the exploitative horror you might expect from the set-up. Deshon has crafted a complex moral fable which, in an era of constant conflict around art and what it means to be free, could not be more timely.

Reviewed on: 26 Aug 2022